According to a recent Time article, Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh, who is considered the father of mindfulness, is close to death, never having fully recovered from the stroke he suffered in 2014.

Although that report has been disputed by Plum Village (the school of Buddhism coming out of the Plum Village Monastery, which Thich Nhat Hanh founded in France), at 92, the monk is certainly frail. He has returned to the temple where he was ordained decades ago, Tu Hieu Pagoda in Hue, Vietnam, to live out the remainder of his time on Earth.

Due to his condition, Thay (“teacher”, as he is affectionately called) is unable to speak, but he still manages to serve as an example of living in the “now” and appreciating every day. Thay is considered one of the greatest teachers of Buddhism and his influence has reaches countless millions.

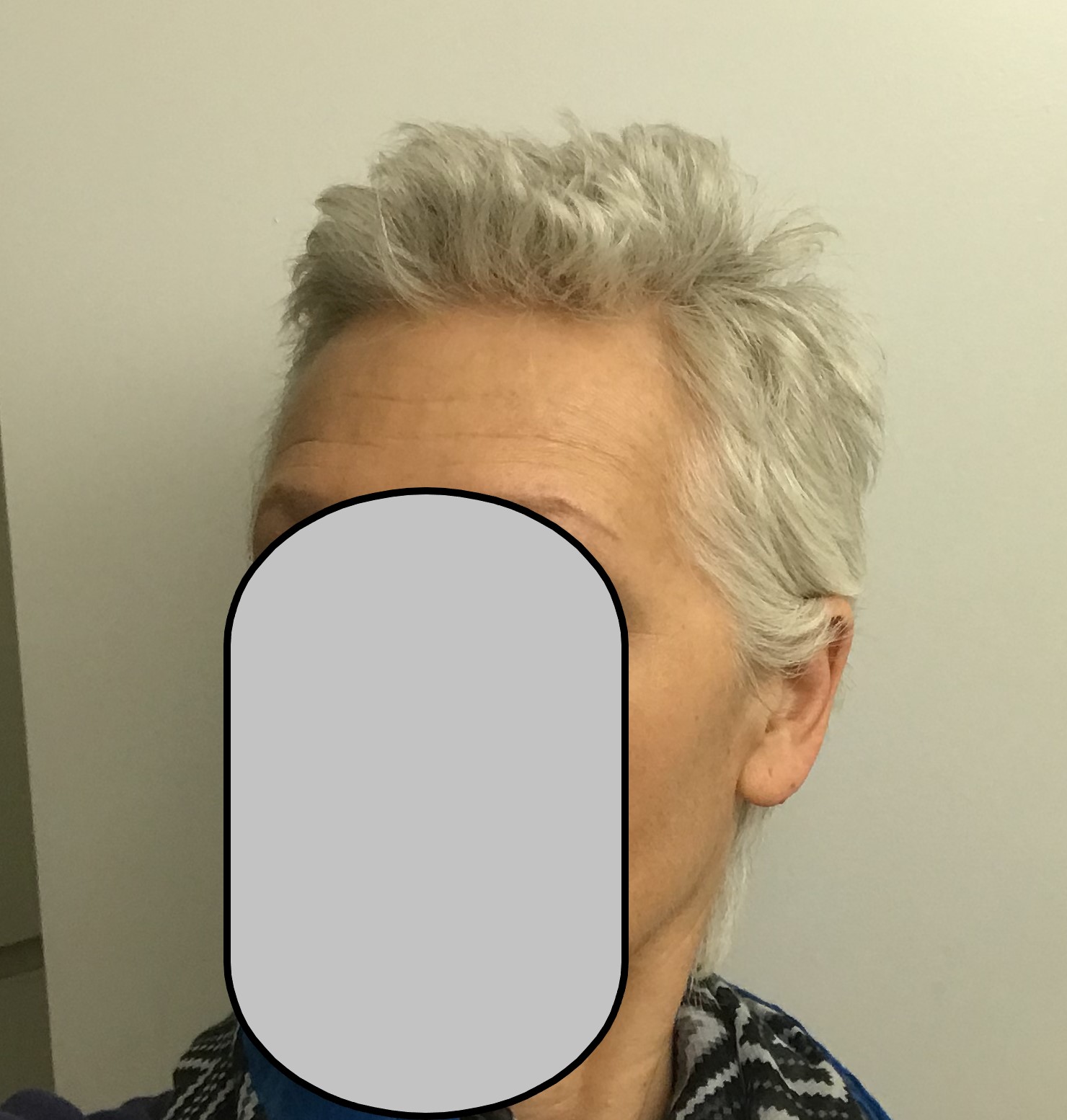

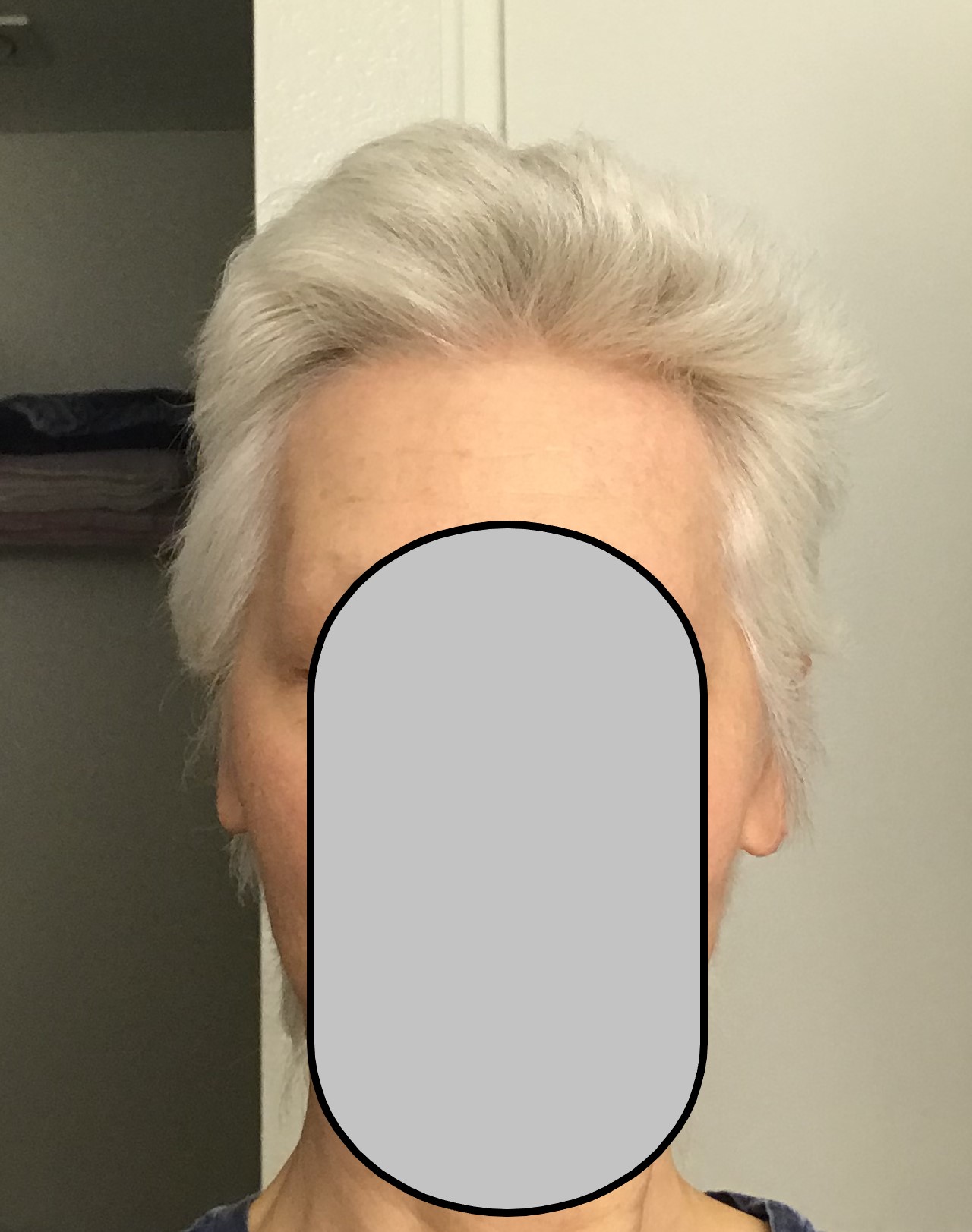

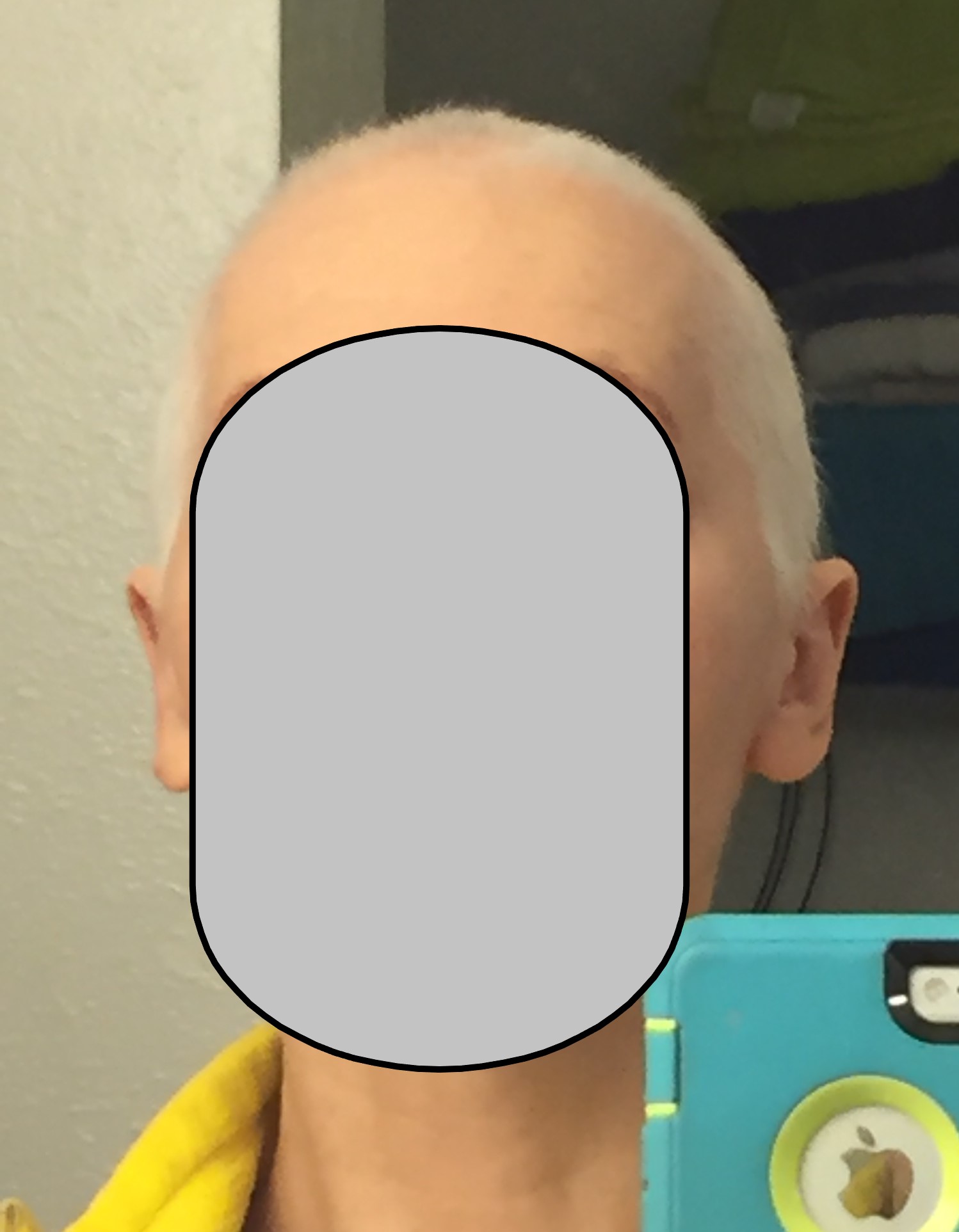

Mindfulness has played a significant role in my life and emotional well-being since my breast cancer diagnosis in early 2017; however, my first exposure to Thich Nhat Hanh was in the early 2000s, during a program called Speaking Of Faith, hosted by Krista Tippett on NPR. I was transfixed as I listened to the story of his life, his anti-war activism during the Vietnam War and his interpretation of Buddhism. We purchased several of his books, specifically the ones he wrote for children: Each Breath A Smile and Under The Rose Apple Tree.

It wasn’t until my cancer experience that Thich Nhat Hanh’s teachings resurfaced in my life. I am deeply indebted to mindfulness for taking me through cancer treatment into recovery and survivorship. And yet, even now, I understand mindfulness in only the most superficial way. Every day of my meditation practice brings me more deeply into it. It has been invaluable not only in dealing with anxiety, but also in cultivating compassion for myself, something that has not come easily.

Most recently, I’ve been utilizing mindfulness to help deal with chemo brain, which continues to plague me. When I feel stupid, can’t remember things or lose concentration, mindfulness provides the way to be more patient and understanding with myself. By staying present, I’m better able to focus. Am I good at it? No, not at all. But I do my best. It’s a process. And if I weren’t practicing mindfulness, I would be in a much worse place.

While I am Roman Catholic, I’ve found that Thich Nhat Hanh’s Buddhism resonates with me, particularly as I watch Christianity struggle with hypocrisy. The practice of mindfulness was the most important gift that I received with my cancer diagnosis, and it allowed me to find even a sliver of peace in what was a dismal situation. I am coming to accept where I am now, not holding on too tightly, but appreciating what I have.